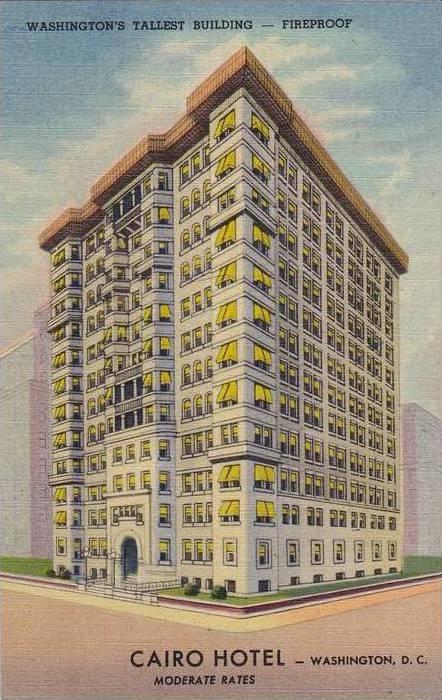

The son of a steeplejack, Reynolds began performing at the age six in Buffalo, New York balancing on one foot from a flagpole 140 feet in the air. His first major stunt came at age 12 when he climbed up the side of the Old South Building in Boston in a hair-raising act, balancing atop four chairs and five tables on a plank projected over the side of the building. Jack Reynolds was one of those death-defying risk-takers who appeared to be fearless. In 1916, he sat on a chair tilted back and balanced on a broomstick suspended between two planks extended over Washington’s tallest building.

Front Page

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, May 26, 2022

Shortly before midnight on Saturday, July 19, 1952, air-traffic controller Edward Nugent at Washington National Airport spotted seven slow-moving objects on his radar screen far from any known civilian or military flight paths. He called over his supervisor and joked about a “fleet of flying saucers.” At the same time, two more air-traffic controllers at National spotted a strange bright light hovering in the distance that suddenly zipped away at incredible speed. At nearby Andrews Air Force Base, radar operators were getting the same unidentified blips—slow and clustered at first, then racing away at speeds exceeding 7,000 mph. Looking out his tower window, one Andrews controller saw what he described as an “orange ball of fire trailing a tail.” A commercial pilot, cruising over the Virginia and Washington, D.C. area, reported six streaking bright lights, “like falling stars without tails.” When radar operators at National watched the objects buzz past the White House and Capitol building, the UFO jokes stopped. Two F-94 interceptor jets were scrambled, but each time they approached the locations appearing on the radar screens, the mysterious blips would disappear. By dawn of July 20, the objects were gone.

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, May 11, 2022

Completed in 1894 as the city’s first skyscraper, the 164ft tall Cairo Flats building prompted local legislation to limit the height of subsequent buildings that continues to shape the District’s skyline. A landmark in the Dupont Circle neighborhood is the Cairo Condominium. It's located at 1615 Q Street, NW, and is the District of Columbia’s tallest residential building. Completed in 1894 as the city’s first skyscraper, the 164ft tall building prompted local legislation to limit the height of subsequent buildings that continues to shape the District’s skyline. Gargoyles and daunting winged creatures hover high above the front entrance, while the stone facade, carved in intricate detail, lends an exotic flavor. Inscribed above its Romanesque Revival arched entrance is the building's name: The Cairo. As charming and unexpected as the Moorish detailing and ghoulish griffins are, it is the Cairo's size relative to its neighbors that is truly its most striking feature.

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, March 29, 2022

In the 1830s, the Baltimore and Ohio Railway built the first train tracks and rail station on the Mall. The B&O operated daily passenger trains on First Street, just below the US Capitol building until 1851. These early trains traveled from Baltimore to Washington in about 2 hours, a trip that takes about 40 minutes today. Watching the new steam rail cars arrive and depart drew Washingtonians from all parts of the city to the brick depot, listening for the arrival and departure bells. After outgrowing its space on the Mall in 1851, the station moved to New Jersey Avenue. Before railroads, it took eleven hours to get from Washington to Baltimore by stagecoach, and 38 hours by stage to Richmond. The District of Columbia's transportation links consisted primarily of Turnpikes and the Potomac River. A small voice was beginning to be heard in transportation circles, a voice that spoke of a new, efficient, speedy form of transportation which rode on rails. Alexandria was an important east coast seaport and was a fierce rival with Baltimore for the traffic of the Shenandoah Valley and the traffic to the South and to the West. Evidently, Baltimore's ears were more sensitive. In 1827 her merchants chartered the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company in the State of Maryland. It would take years to determine that this would doom Alexandria as a seaport power.

- Posted by : Staff Writer, March 16, 2022

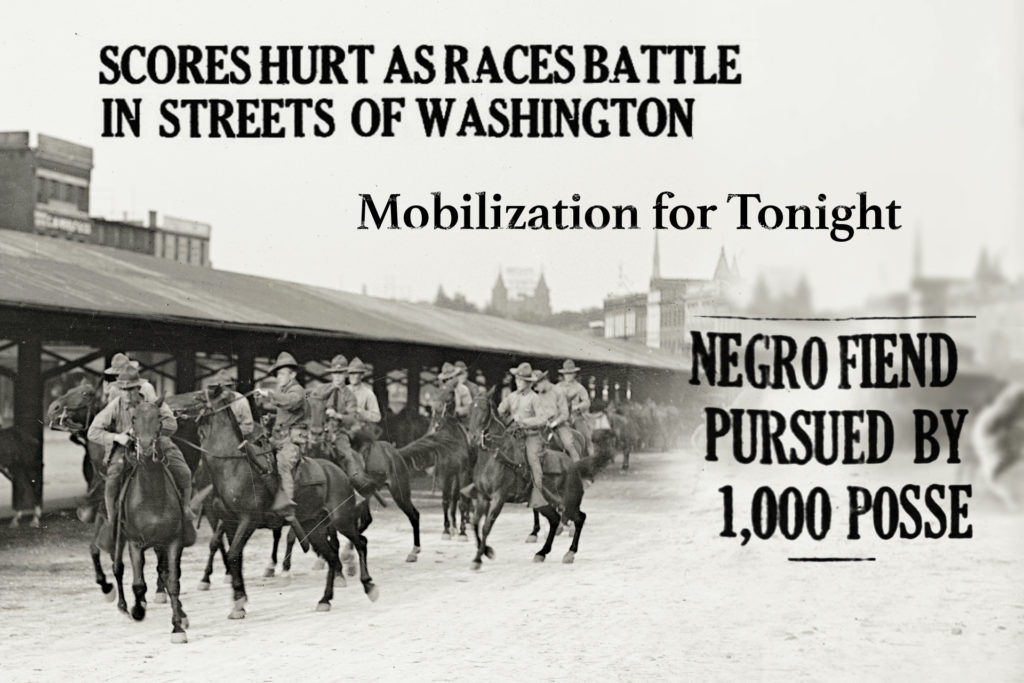

The nation’s capital was at war with itself. On a muggy Saturday night in July 1919, white veterans were drinking in the bars clustered downtown when their banter gave birth to a rumor. The Metropolitan Police Department had arrested, questioned, and released a black man suspected of sexually assaulting a white woman—and not just any white woman, either, but the wife of a Navy man. The story snaked through the packed saloons and pool halls.

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, March 09, 2022

When airmail began in 1918, airplanes were still a relatively new invention. Pilots flew in open cockpits in all kinds of weather, in planes later described as "a nervous collection of whistling wires, of linen stretched over wooden ribs, all attached to a wheezy, water-cooled engine." A 1918 article titled "Practical Hints on Flying" advised pilots to "never forget that the engine may stop, and at all times keep this in mind." Pilots followed landmarks on the ground; in the fog, they flew blind. Unpredictable weather, unreliable equipment, and inexperience led to frequent crashes; 34 airmail pilots died from 1918 through 1927. Gradually, through trial and error and personal sacrifice, U.S. Air Mail Service employees developed reliable navigation aids and safety features for planes and pilots. They demonstrated that flight schedules could be safely maintained in all kinds of weather.

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, February 23, 2022

Throughout its history, Washington, DC has been the destination of demonstrators seeking to promote a wide variety of causes. The January 6th attack on the capitol is just the latest example. In March of 1932, another large group of protestor/patriots came demand the Bonus pay they'd earned during World War One. After victory in World War I, the US government promised in 1924 that servicemen would receive a bonus for their service if they could wait until 1945. In March of 1932, another large group of protestors came to demand the Bonus pay they'd earned during World War One. The Great Depression was on, and the U.S. Treasury was strapped for cash. By 1932, the Depression was dragging on, with no end in sight. Out of sheer desperation, some of the veterans decided to march on Washington to ask for the bonus right away.

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, January 29, 2022

During the War of 1812, Reuben Daw, a Georgetown merchant, loaned the War Department money to help defend the Capital during the British invasion. Following the War, when the Department was unable to re-pay the loan, Daw and other creditors were offered surplus military gear as payment in kind. Daw wanted to build a fence around his four homes on P and 28 Street. It became a tourist attraction, if not exactly beating swords into ploughshares...

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, October 27, 2021

A Bicycle Built for Two was a popular love song composed in 1892 – in the happier and more carefree days once known as the “Gay-90’s.” It was a peaceful time – before the automobile – when the bicycle beat out the horse as the best way to get around. The bicycle became part of a grassroots recreation movement, with people using leisure time to get out of the city and into the country. In the 1880s, High-wheel bicycles had been new and popular. Even though they were heavy, made of iron and wood, and dangerously hard to ride. now know how the bicycle emancipated women, but it wasn’t exactly a smooth ride. The following list of 41 don’ts for female cyclists was published in 1895 in the newspaper New York World by an author of unknown gender. Equal parts amusing and appalling, the list is the best (or worst, depending on you look at it) thing since the Victorian map of woman’s heart. Don’t be a fright. Don’t faint on the road. Don’t wear a man’s cap. Don’t wear tight garters. Don’t forget your toolbag Don’t attempt a “century.” Don’t coast. It is dangerous. Don’t boast of your long rides. Don’t criticize people’s “legs.” Don’t wear loud hued leggings. Don’t cultivate a “bicycle face.” Don’t refuse assistance up a hill. Don’t wear clothes that don’t fit. Don’t neglect a “light’s out” cry. Don’t wear jewelry while on a tour. Don’t race. Leave that to the scorchers. Don’t wear laced boots. They are tiresome. Don’t imagine everybody is looking at you. Don’t go to church in your bicycle costume. Don’t wear a garden party hat with bloomers. Don’t contest the right of way with cable cars. Don’t chew gum. Exercise your jaws in private. Don’t wear white kid gloves. Silk is the thing. Don’t ask, “What do you think of my bloomers?” Don’t use bicycle slang. Leave that to the boys. Don’t go out after dark without a male escort. Don’t go without a needle, thread and thimble. Don’t try to have every article of your attire “match.” Don’t let your golden hair be hanging down your back. Don’t allow dear little Fido to accompany you Don’t scratch a match on the seat of your bloomers. Don’t discuss bloomers with every man you know. Don’t appear in public until you have learned to ride well. Don’t overdo things. Let cycling be a recreation, not a labor. Don’t ignore the laws of the road because you are a woman. Don’t try to ride in your brother’s clothes “to see how it feels.” Don’t scream if you meet a cow. If she sees you first, she will run. Don’t cultivate everything that is up to date because yon ride a wheel. Don’t emulate your brother’s attitude if he rides parallel with the ground. Don’t undertake a long ride if you are not confident of performing it easily. Don’t appear to be up on “records” and “record smashing.” That is sporty.

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, October 05, 2021

“Swampoodle” was the term originally applied to the settlement along H Street near the Tiber (between North Capitol and First Street, East), and finally it included Pearce’s meadow, a great hunting ground extending to the boundary of the city. … In recent years the eastern line of the ‘poodle’ has been contracted to the limits of G, K, Fourth, East, and First Streets, West. . . .” The name was applied in the 1850s, although when exactly is unknown. Swampoodle was a neighborhood in Washington, D.C. on the border of Northwest and Northeast in the second half of 19th and early 20th century. This neighborhood is no longer known as Swampoodle and has been replaced in large part by NoMa.

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, September 07, 2021

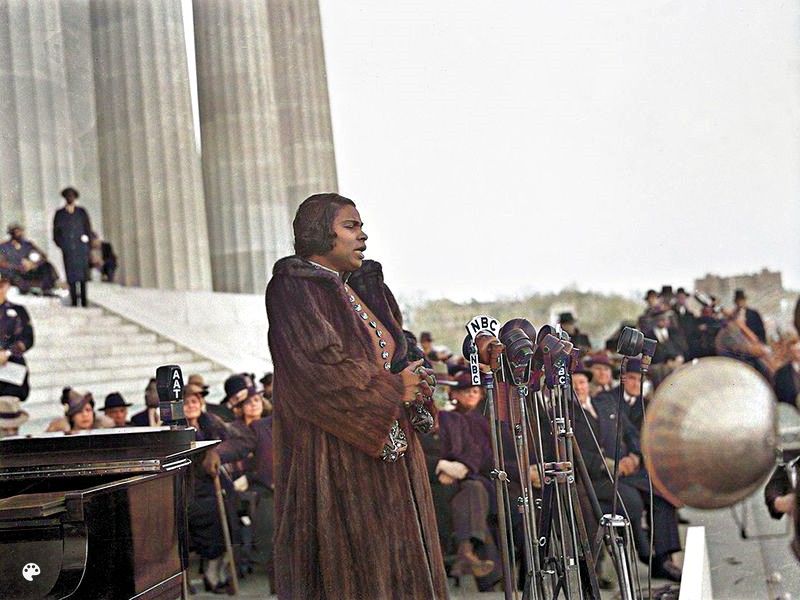

It was Easter Sunday on April 9, 1939. One of the world’s greatest singers, contralto Marian Anderson, had been denied permission to sing at Constitution Hall, owned by the Daughters of the American Revolution, because of her race. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt quit the D.A.R. over the racist action and helped change the venue to the Lincoln Memorial. The incident placed the respected contralto into a spotlight unusual for a classical musician of the time. 75,000 people were in the audience that day. She was terrified. Later, she wrote: “I could not run away from this situation. If I had anything to offer, I would have to do so now.” And some one-hundred thousand Washingtonians joined Ms. Roosevelt in giving the stuffy organization the finger.

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, November 29, 1921

Margaret Gorman was a junior at Western High School in Washington, D.C. when her photo was entered into a popularity contest at the Washington Herald. She was chosen as “Miss District of Columbia” in 1921 at age 16 on account of her athletic ability, past accomplishments, and outgoing personality. As a result of that victory, she was invited to join the Second Annual Atlantic City Pageant held on September 8, 1921, as an honored guest. There she was invited to join a new event: the “Inter-City Beauty” Contest. She won the titles “Inter-City Beauty, Amateur” and “The Most Beautiful Bathing Girl in America” after competing in the Bather’s Revue. She won the grand prize, the Golden Mermaid trophy. She was expected to defend her positions the next year, but someone else[who?] had attained the title of “Miss Washington, D.C.,” so she was instead crowned as “Miss America.” She is the only Miss America to receive her crown at the end of the year. Gorman was the lightest Miss America at 108 pounds until 1949, when Jacque Mercer of Phoenix, Arizona, weighed in at 106 and won the title. Gorman later said: “I never cared to be Miss America. It wasn’t my idea. I am so bored by it all. I really want to forget the whole thing.” She still owned the sea green chiffon and sequined dress that she wore in the 1922 competition.