- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, January 16, 2023

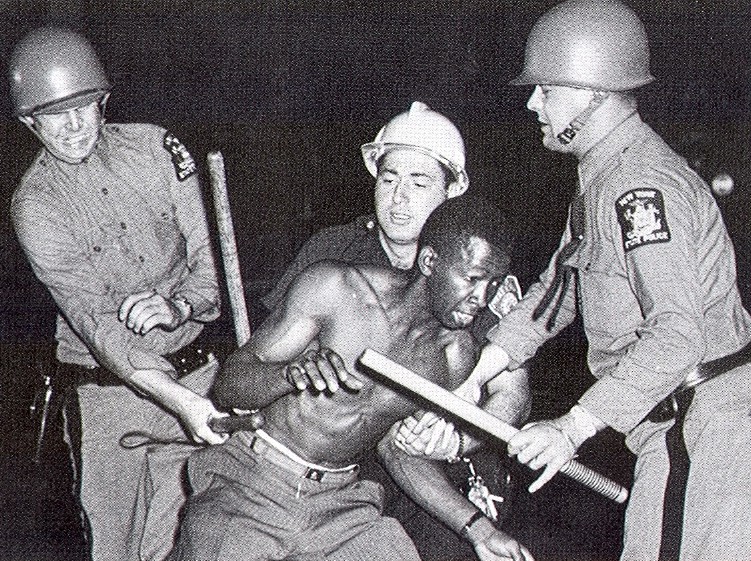

African Americans have been a significant part of Washington, DC's civic life and identity since the city was first declared the new national capital in 1791. African Americans were 25 percent of the population in 1800, and the majority of them were enslaved. By 1830, however, most were free people. Yet slavery remained. African Americans, of course, resisted slavery and injustice by organizing churches, private schools, aid societies, and businesses; by amassing wealth and property; by leaving the city; and by demanding abolition. In 1848, 77 free and enslaved adults and children unsuccessfully attempted the nation's largest single escape aboard the schooner Pearl. On April 16, 1862, Congress passed the District of Columbia Emancipation Act, making Washingtonians the first freed in the nation, nine months before President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863. Congress had the authority to pass the DC Emancipation Act because it was granted the power to "exercise exclusive legislation" over the federal district by the U.S. Constitution. This federal oversight has been a source of conflict throughout Washington's history.During the Civil War (1861-1865) and Reconstruction (1865-1877), more than 25,000 African Americans moved to Washington. The fact that it was mostly pro-Union and the nation's capital made it a popular destination. Through the passage of Congress's Reconstruction Act of 1867, the city's African American men gained the right to vote three years before the passage of the 15th amendment gave all men the right to vote. (Women gained the right to vote in 1920.) The first black municipal office holder was elected in 1868. When Washington briefly became a federal territory in 1871, African American men continued to make important decisions for the city. Lewis H. Douglass introduced the 1872 law making segregation in public accommodations illegal. But in 1874, in part because of growing black political power, the territorial government was replaced by three presidentially appointed commissioners. This system survived until the civil rights movement of the 1960s brought a measure of self-government. By 1900 Washington had the largest percentage of African Americans of any city in the nation. Many came because of opportunities for federal jobs. Others were attracted to the myriad educational institutions. Howard University, founded in 1867, was a magnet for professors and students and would become the "capstone of Negro education" by 1930. The Preparatory School for Colored Youth, the city's first public high school, attracted college-bound students and teachers, many with advanced degrees. (Founded in 1870, the school became renowned as M Street High School, and later, Dunbar High School.) As far back as 1814, churches had operated and supported schools and housed literary and historical societies that promoted critical thinking, reading, lecturing, and social justice. African Americans also created hundreds of black-owned businesses and numerous business districts. At the dawn of the 20th century, African Americans had created a cultural and intellectual capital. Washington had relatively few "Jim Crow" laws. However, segregation and racism were endemic. The few existing laws mandated segregation in the public schools and recreation facilities but not in the streetcars and public libraries. African Americans, therefore, reacted strongly to President Wilson's (1913-1921) institution of segregation in all of the federal government agencies. Clashes between African Americans and European Americans reached a fever pitch during the July 1919 race riot, when women and men fought back against violent whites, giving another meaning to the term "New Negro," a term usually associated with the cultural renaissance of the 1920s and 1930s. During the Great Depression (1929-1939) and World War II (1939-1945), the early civil rights movement gained ground. In 1933, the same year that President Franklin Roosevelt (1933-1945) began to end segregation in the federal government, the young black men of the New Negro Alliance instituted "Don't Buy Where You Can't Work" campaigns against racist hiring practices in white-owned stores in predominantly black neighborhoods. The Washington chapter of the National Negro Congress also organized against police brutality and segregation in recreation beginning in 1936. The "Double V" effort - Victory Abroad, Victory at Home - increased civil rights activity. In 1943 Howard University law student Pauli Murray led coeds in a sit-in at the Little Palace cafeteria, a white-trade-only business near 14th and U streets, NW, an area that was largely African American. In 1948 the Supreme Court declared racially restrictive housing covenants were unconstitutional in the local Hurd v. Hodge case. Beginning in 1949 Mary Church Terrell led a multiracial effort to end segregation in public accommodations through pickets, boycotts, and legal action. Four years later, in District of Columbia v. John R. Thompson Co., the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that segregation in Washington was unconstitutional based on the 1872 law passed during Reconstruction but long forgotten. In 1954 a local case, Bolling v. Sharpe, was part of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision, which declared separate education was unconstitutional. In 1957 Washington's African American population surpassed the 50 percent mark, making it the first predominantly black major city in the nation, and leading a nationwide trend. The 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom brought more than 250,000 people to the Lincoln Memorial. Its success was helped by the support and contributions of local churches and organizations. The assassination of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., on April 4, 1968, triggered immediate and intense reactions throughout the nation and the city. During the 1968 riots, when buildings were burned and destroyed, many African Americans rebelled against continued racism, injustice, and the federal government's abandonment of the city. Even before Dr. King's assassination, demands for justice undoubtedly helped push the federal government to take first steps towards "home rule" by appointing Walter Washington as mayor in 1967. In 1974 residents chose Washington as the city's first elected black mayor and the first mayor of the 20th century. By 1975 African Americans were politically and culturally leading the city with more than 70 percent of the population. The Black Arts, Black Power, Women's, and Statehood movements flowered here. Indeed, Marion Barry, who succeeded Washington as mayor, began his public life here as a leader of local justice movements. There were independent think tanks, schools, bookstores, and repertory companies. Go-go (DC's home-grown version of funk) as well as jazz, blues, and salsa, resonated from clubs, parks, recreation centers, and car radios. With the uniting of political activism and creativity, African Americans were transforming the city once again. *Reprinted from Marya Annette McQuirter, African American Heritage Trail, Washington, DC (Washington: Cultural Tourism DC, 2003).

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, July 27, 2022

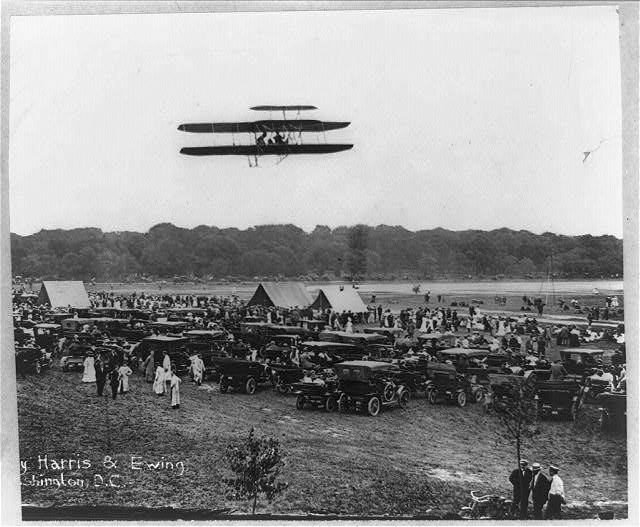

The 1909 Wright Military Flyer is the world's first military airplane. In 1908, the U.S. Army Signal Corps sought competitive bids for a two-seat observation aircraft. Winning designs had to meet a number specified performance standards. Flight trials with the Wrights' entry began at Fort Myer, Virginia, on September 3, 1908. After several days of successful flights, tragedy occurred on September 17, when Orville Wright crashed with Lt. Thomas E. Selfridge, the Army's observer, as his passenger. Orville survived with severe injuries, but Selfridge was killed, becoming the first fatality in a powered airplane. On June 3, 1909, the Wrights returned to Fort Myer with a new airplane to complete the trials begun in 1908. Satisfying all requirements, the Army purchased the airplane for $30,000, and conducted flight training with it at nearby College Park, Maryland, and at Fort Sam Houston, in San Antonio, Texas, in 1910. It was given to the Smithsonian in 1911.

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, May 26, 2022

Shortly before midnight on Saturday, July 19, 1952, air-traffic controller Edward Nugent at Washington National Airport spotted seven slow-moving objects on his radar screen far from any known civilian or military flight paths. He called over his supervisor and joked about a “fleet of flying saucers.” At the same time, two more air-traffic controllers at National spotted a strange bright light hovering in the distance that suddenly zipped away at incredible speed. At nearby Andrews Air Force Base, radar operators were getting the same unidentified blips—slow and clustered at first, then racing away at speeds exceeding 7,000 mph. Looking out his tower window, one Andrews controller saw what he described as an “orange ball of fire trailing a tail.” A commercial pilot, cruising over the Virginia and Washington, D.C. area, reported six streaking bright lights, “like falling stars without tails.” When radar operators at National watched the objects buzz past the White House and Capitol building, the UFO jokes stopped. Two F-94 interceptor jets were scrambled, but each time they approached the locations appearing on the radar screens, the mysterious blips would disappear. By dawn of July 20, the objects were gone.

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, May 11, 2022

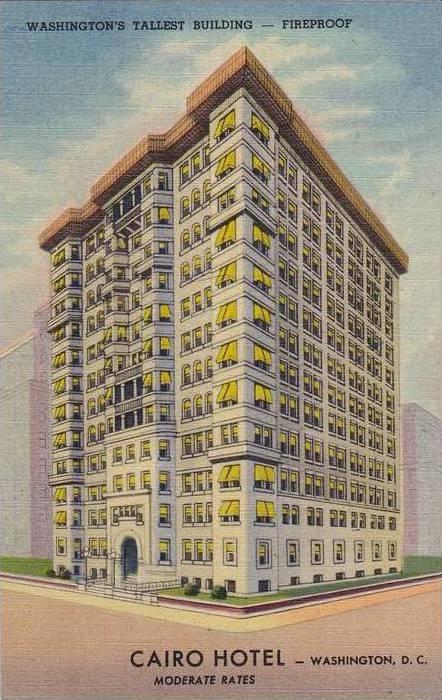

Completed in 1894 as the city’s first skyscraper, the 164ft tall Cairo Flats building prompted local legislation to limit the height of subsequent buildings that continues to shape the District’s skyline. A landmark in the Dupont Circle neighborhood is the Cairo Condominium. It's located at 1615 Q Street, NW, and is the District of Columbia’s tallest residential building. Completed in 1894 as the city’s first skyscraper, the 164ft tall building prompted local legislation to limit the height of subsequent buildings that continues to shape the District’s skyline. Gargoyles and daunting winged creatures hover high above the front entrance, while the stone facade, carved in intricate detail, lends an exotic flavor. Inscribed above its Romanesque Revival arched entrance is the building's name: The Cairo. As charming and unexpected as the Moorish detailing and ghoulish griffins are, it is the Cairo's size relative to its neighbors that is truly its most striking feature.

- Posted by : Staff Writer, April 13, 2022

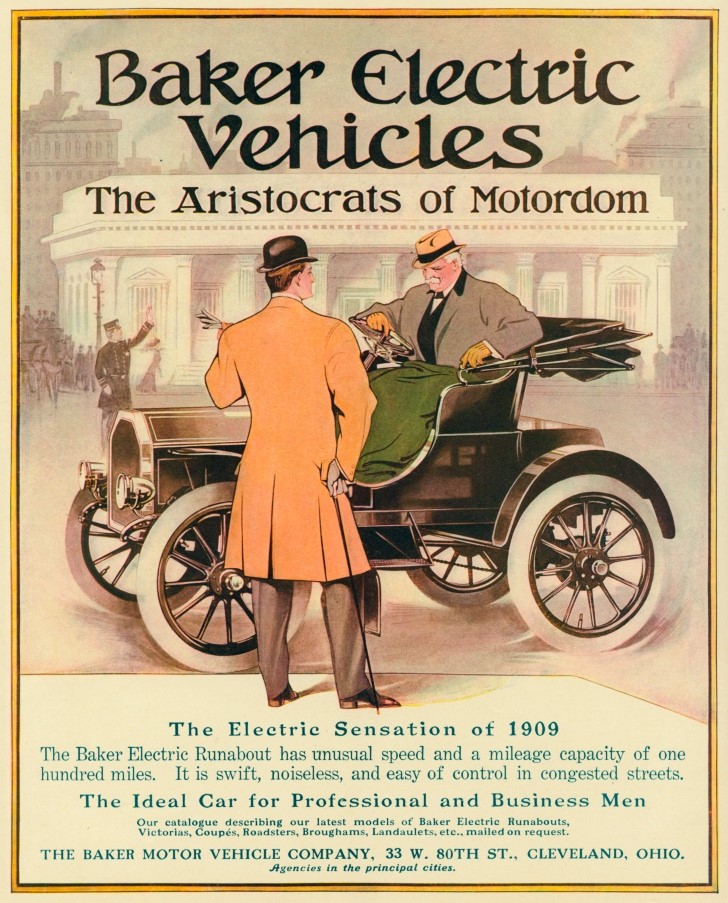

The electric car burst onto the scene in the late 1800s and early 1900s. In 1899 and 1900, electric vehicles outsold all other types of cars. In fact, 28 percent of all 4,192 cars produced in the US in 1900 were electric, according to the American Census. Sales of electric cars peaked in the early 1910s. There were over 300 listed manufacturers who produced a vehicle in the United States upto 1942. Practical electric vehicles appeared during the 1890s. An electric vehicle held the vehicular land speed record until around 1900. In the 20th century, the high cost, low top speed, and short range of battery electric vehicles, compared to internal combustion engine vehicles, led to a worldwide decline in their use as private motor vehicles. Electric vehicles have continued to be used for loading and freight equipment and for public transport – especially rail vehicles.What is likely the first human-carrying electric vehicle with its own power source was tested along a Paris street in April 1881 by French inventor Gustave Trouvé.[20] In 1880 Trouvé improved the efficiency of a small electric motor developed by Siemens (from a design purchased from Johann Kravogl [de] in 1867) and using the recently developed rechargeable battery, fitted it to an English James Starley tricycle, so inventing the world's first electric vehicle.[21] Although this was successfully tested on 19 April 1881 along the Rue Valois in central Paris, he was unable to patent it.[22] Trouvé swiftly adapted his battery-powered motor to marine propulsion; to make it easy to carry his marine conversion to and from his workshop to the nearby River Seine, Trouvé made it portable and removable from the boat, thus inventing the outboard motor. On 26 May 1881, the 5-metre Trouvé boat prototype, called Le Téléphone reached a speed of 3.6 km/h (2.2 mph) going upstream and 9.0 km/h (5.6 mph) downstream.[23] English inventor Thomas Parker, who was responsible for innovations such as electrifying the London Underground, overhead tramways in Liverpool and Birmingham, and the smokeless fuel coalite, built his first electric car in Wolverhampton in 1884, although the only documentation is a photograph from 1895.[24] Parker's long-held interest in the construction of more fuel-efficient vehicles led him to experiment with electric vehicles. He also may have been concerned about the malign effects smoke and pollution were having in London.[25] Production of the car was in the hands of the Elwell-Parker Company, established in 1882 for the construction and sale of electric trams. The company merged with other rivals in 1888 to form the Electric Construction Corporation; this company had a virtual monopoly on the British electric car market in the 1890s. The company manufactured the first electric 'dog cart' in 1896.[26] France and the United Kingdom were the first nations to support the widespread development of electric vehicles.[8] German engineer Andreas Flocken built the first real electric car in 1888.[27][28][29][30] Electric trains were also used to transport coal out of mines, as their motors did not use up precious oxygen. Before the pre-eminence of internal combustion engines, electric automobiles also held many speed and distance records.[31] Among the most notable of these records was the breaking of the 100 km/h (62 mph) speed barrier, by Camille Jenatzy on 29 April 1899 in his 'rocket-shaped' vehicle Jamais Contente, which reached a top speed of 105.88 km/h (65.79 mph). Also notable was Ferdinand Porsche's design and construction of an all-wheel drive electric car, powered by a motor in each hub, which also set several records in the hands of its owner E.W. Hart. The first electric car in the United States was developed in 1890–91 by William Morrison of Des Moines, Iowa; the vehicle was a six-passenger wagon capable of reaching a speed of 23 kilometres per hour (14 mph). It was not until 1895 that consumers began to devote attention to electric vehicles after A.L. Ryker introduced the first electric tricycles to the U.S.[32] Golden age Interest in motor vehicles increased greatly in the late 1890s and early 1900s. Electric battery-powered taxis became available at the end of the 19th century. In London, Walter Bersey designed a fleet of such cabs and introduced them to the streets of London in 1897.[33] They were soon nicknamed "Hummingbirds" due to the idiosyncratic humming noise they made.[34] In the same year in New York City, the Samuel's Electric Carriage and Wagon Company began running 12 electric hansom cabs.[35] The company ran until 1898 with up to 62 cabs operating until it was reformed by its financiers to form the Electric Vehicle Company.[36] Thomas Edison and an electric car in 1913 Electric vehicles had a number of advantages over their early-1900s competitors. They did not have the vibration, smell, and noise associated with gasoline cars. They also did not require gear changes. (While steam-powered cars also had no gear shifting, they suffered from long start-up times of up to 45 minutes on cold mornings.) The cars were also preferred because they did not require a manual effort to start, as did gasoline cars which featured a hand crank to start the engine. Electric cars found popularity among well-heeled customers who used them as city cars, where their limited range proved to be even less of a disadvantage. 1912 Detroit Electric advertisement Acceptance of electric cars was initially hampered by a lack of power infrastructure.[37] In the United States by the turn of the century, 40 percent of automobiles were powered by steam, 38 percent by electricity, and 22 percent by gasoline. A total of 33,842 electric cars were registered in the United States, and the U.S. became the country where electric cars had gained the most acceptance.[38] Most early electric vehicles were massive, ornate carriages designed for the upper-class customers that made them popular. They featured luxurious interiors and were replete with expensive materials. Electric vehicles were often marketed as a women’s luxury car, which may have been a stigma among male consumers.[39] Sales of electric cars peaked in the early 1910s. There were over 300 listed manufacturers who produced a vehicle in the United States upto 1942.[40] At the beginning of the 21st century, interest in electric and alternative fuel vehicles in private motor vehicles increased due to: growing concern over the problems associated with hydrocarbon-fueled vehicles, including damage to the environment caused by their emissions; the sustainability of the current hydrocarbon-based transportation infrastructure; and improvements in electric vehicle technology. Since 2010, combined sales of all-electric cars and utility vans achieved 1 million units delivered globally in September 2016,[1] 4.8 million electric cars in use at the end of 2019,[2] and cumulative sales of light-duty plug-in electric cars reached the 10 million unit milestone by the end of 2020.[3] The global ratio between annual sales of battery electric cars and plug-in hybrids went from 56:44 in 2012 to 74:26 in 2019, and fell to 69:31 in 2020.[3][4][5] As of August 2020, the fully electric Tesla Model 3 is the world's all-time best selling plug-in electric passenger car, with around 645,000 units.[6] Contents 1 Early history 1.1 Electric model cars 1.2 Electric locomotives 2 First full-scale electric cars 3 Golden age 3.1 Power as a service and General Vehicle 4 1920s–1950s 5 1960s–1990s: Revival of interest 6 2000s: Modern highway-capable electric cars 7 2010s 8 2020s 9 Electric bicycle 10 Timeline of milestones 11 Notable production vehicles 12 See also 13 References 14 External links

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, March 29, 2022

In the 1830s, the Baltimore and Ohio Railway built the first train tracks and rail station on the Mall. The B&O operated daily passenger trains on First Street, just below the US Capitol building until 1851. These early trains traveled from Baltimore to Washington in about 2 hours, a trip that takes about 40 minutes today. Watching the new steam rail cars arrive and depart drew Washingtonians from all parts of the city to the brick depot, listening for the arrival and departure bells. After outgrowing its space on the Mall in 1851, the station moved to New Jersey Avenue. Before railroads, it took eleven hours to get from Washington to Baltimore by stagecoach, and 38 hours by stage to Richmond. The District of Columbia's transportation links consisted primarily of Turnpikes and the Potomac River. A small voice was beginning to be heard in transportation circles, a voice that spoke of a new, efficient, speedy form of transportation which rode on rails. Alexandria was an important east coast seaport and was a fierce rival with Baltimore for the traffic of the Shenandoah Valley and the traffic to the South and to the West. Evidently, Baltimore's ears were more sensitive. In 1827 her merchants chartered the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company in the State of Maryland. It would take years to determine that this would doom Alexandria as a seaport power.

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, March 09, 2022

When airmail began in 1918, airplanes were still a relatively new invention. Pilots flew in open cockpits in all kinds of weather, in planes later described as "a nervous collection of whistling wires, of linen stretched over wooden ribs, all attached to a wheezy, water-cooled engine." A 1918 article titled "Practical Hints on Flying" advised pilots to "never forget that the engine may stop, and at all times keep this in mind." Pilots followed landmarks on the ground; in the fog, they flew blind. Unpredictable weather, unreliable equipment, and inexperience led to frequent crashes; 34 airmail pilots died from 1918 through 1927. Gradually, through trial and error and personal sacrifice, U.S. Air Mail Service employees developed reliable navigation aids and safety features for planes and pilots. They demonstrated that flight schedules could be safely maintained in all kinds of weather.

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, March 04, 2022

It was one of Washington's most spectacular fires. It happened on September 29, 1897, at the Capital Traction Company's powerhouse at 14th and E Northwest. It is now the site of the John Wilson Building, the Council of the District of Columbia. The company replaced the cable cars it served with an electric system, using horses in the interim. The electric wire for the cars was placed in the old cable system's underground conduit. The 14th Street branch switched to electric power on February 27, 1898, the Pennsylvania Avenue division on April 20, 1898 (March 20 west of the Capitol), and the 7th Street branch on May 26, 1898. The place where cars changed between Capital Traction and Metropolitan was initially located at U and 18th Streets. It was moved just east of the bridge over Rock Creek - to the Calvert Street Loop - in the spring of 1899 when the conduit system was changed to the more standard and less expensive contact shoe. The old line on Florida Avenue between 18th and Connecticut was discontinued that year and the track removed. On September 29, 1897, the Capital Traction Company's powerhouse at 14th and E NW burned down - and almost took downtown DC with it. Today, the location is taken by the John Wilson Building, the Council of the District of Columbia. After the conflagration, the company replaced the cable cars it served with an electric system, using horses in the interim. The electric wire for the cars was placed in the old cable system's underground conduit. The 14th Street branch switched to electric power on February 27, 1898, the Pennsylvania Avenue division on April 20, 1898 (March 20 west of the Capitol),[5] and the 7th Street branch on May 26, 1898. The place where cars changed between Capital Traction and Metropolitan was initially located at U and 18th Streets. It was moved to just east of the bridge over Rock Creek - to the Calvert Street Loop - in the spring of 1899 when the conduit system was changed to the more standard and less expensive contact shoe.[6] The old line on Florida Avenue between 18th and Connecticut was discontinued that year and the track removed.---- On yesterday's date in 1897, fire destroyed the Capital Traction Powerhouse at 14th/Penn. All that remained was a sign reading "Absolutely Fireproof." Less known: "Capital Traction Powerhouse" was an in-house Council funk band in the 70s. In 1908, our building was built t/here.

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, February 23, 2022

Throughout its history, Washington, DC has been the destination of demonstrators seeking to promote a wide variety of causes. The January 6th attack on the capitol is just the latest example. In March of 1932, another large group of protestor/patriots came demand the Bonus pay they'd earned during World War One. After victory in World War I, the US government promised in 1924 that servicemen would receive a bonus for their service if they could wait until 1945. In March of 1932, another large group of protestors came to demand the Bonus pay they'd earned during World War One. The Great Depression was on, and the U.S. Treasury was strapped for cash. By 1932, the Depression was dragging on, with no end in sight. Out of sheer desperation, some of the veterans decided to march on Washington to ask for the bonus right away.

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, January 29, 2022

During the War of 1812, Reuben Daw, a Georgetown merchant, loaned the War Department money to help defend the Capital during the British invasion. Following the War, when the Department was unable to re-pay the loan, Daw and other creditors were offered surplus military gear as payment in kind. Daw wanted to build a fence around his four homes on P and 28 Street. It became a tourist attraction, if not exactly beating swords into ploughshares...

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, January 29, 2022

The 1920s is also known as the Jazz era. With the music industry just beginning the likes of Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington were hugely popular. Art changed with the start of the Art Deco influence. This was seen through stained glass windows all the way to architecture. Famous architects include Frank Lloyd Wright and the design company Bauhaus who structured buildings and interiors with linear lines. The Art Deco influences gave clear inspiration to twenties fashion: the structured lines, squares, and pyramid shapes from the architecture can be clearly identified in the style of the short, drop-shouldered dresses popular for the period.+

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, November 17, 2021

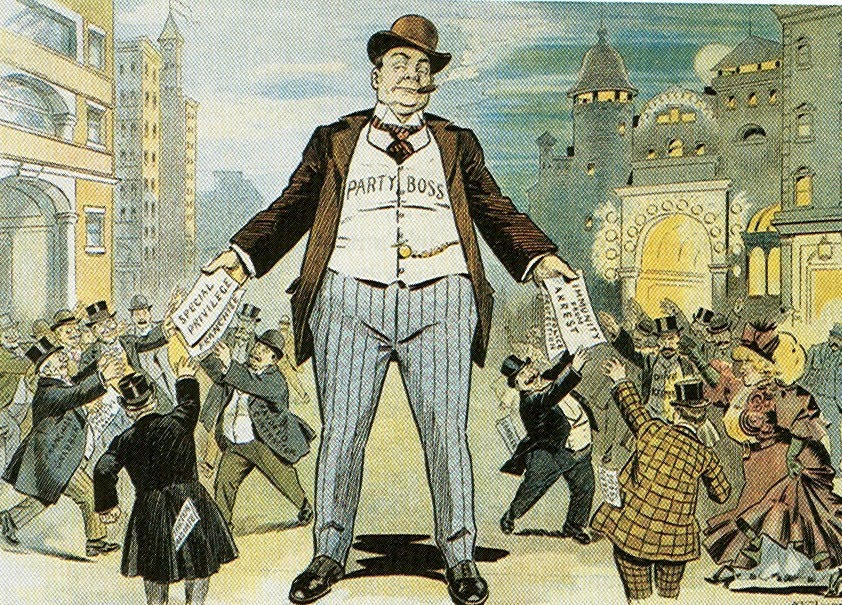

The Gilded Age in America was an era of rapid economic growth, and as wages grew much higher than in Europe, there was a huge influx of immigrants. In one generation a nation of farms, workshops, and small towns had become a society of cities, factories, and intricate social and economic organizations. Until late into the 19th century, newcomers to Washington largely were domestic migrants, particularly Southern blacks. During a time when other cities saw their foreign-born populations skyrocket, Washington’s immigrant population remained comparatively small. In 1900, Washington’s population was only 7 percent foreign-born, compared to Boston’s population of 35 percent foreign-born, New York’s was 37 percent, and Philadelphia’s was 23 percent. (Click)

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, November 02, 2021

Over the past two years, historians and analysts have compared the coronavirus to the 1918 flu pandemic. Many of the mitigation practices used to combat the spread of the coronavirus, especially before the development of the vaccines, have been the same as those used in 1918 and 1919 — masks and hygiene, social distancing, ventilation, limits on gatherings (especially indoors), quarantines, mandates, closure policies and more. The takeaway: Fatigue and removing mitigation methods made things worse. Public officials needed to safeguard the public good, even if that meant unpopular moves. The flu burned through vulnerable populations, but by late winter and early spring 1919, deaths and infections dropped rapidly, shifting toward an endemic moment — the flu would remain present, but less deadly and dangerous. Overall, nearly 675,000 Americans died during the 1918-19 flu pandemic, the majority during the second wave in the autumn of 1918. (writer: Christopher Nichols, Andrew Carnegie Fellow) And from CDC: The 1918 influenza pandemic was the most severe pandemic in recent history. It was caused by an H1N1 virus with genes of avian origin. Although there is not universal consensus regarding where the virus originated, it spread worldwide during 1918-1919. In the United States, it was first identified in military personnel in spring 1918. It is estimated that about 500 million people or one-third of the world’s population became infected with this virus. The number of deaths was estimated to be at least 50 million worldwide with about 675,000 occurring in the United States. Mortality was high in people younger than 5 years old, 20-40 years old, and 65 years and older. The high mortality in healthy people, including those in the 20-40 year age group, was a unique feature of this pandemic. While the 1918 H1N1 virus has been synthesized and evaluated, the properties that made it so devastating are not well understood. With no vaccine to protect against influenza infection and no antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial infections that can be associated with influenza infections, control efforts worldwide were limited to non-pharmaceutical interventions such as isolation, quarantine, good personal hygiene, use of disinfectants, and limitations of public gatherings, which were applied unevenly.

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, November 01, 2021

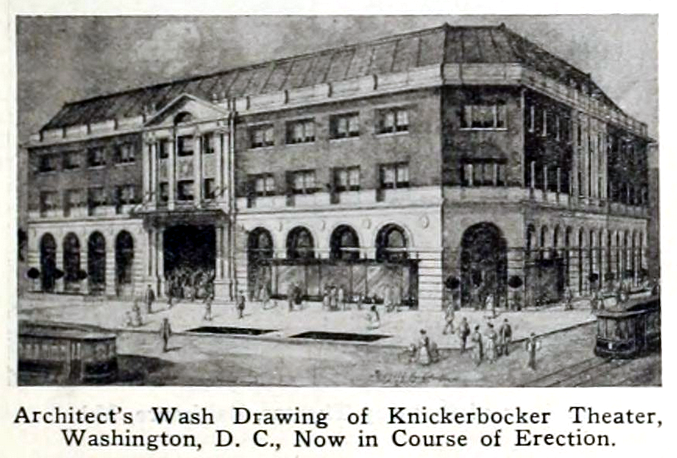

From cinema treasures The Knickerbocker Theatre opened on October 12, 1917, with the historical drama “Betsy Ross” and an appearance by the film’s star, Alice Brady. On January 28, 1922, during an intermission in the hit comedy film, “Get Rich Quick Wallingford”, while the orchestra was playing, the Knickerbocker Theatre’s poorly constructed roof collapsed after a heavy snowstorm over the past two days had piled almost two feet of snow on it. After the cave-in, 98 people were killed and 136 injured, in what was then Washington’s worst disaster. Crandall closed all of his theatres in sympathy for the dead after the Knickerbocker Theatre disaster for a week, and was not charged with any wrongdoing, which was not the case of Reginald W. Geare, whose career as the most popular theatre architect in the District of Columbia up until that time came to an abrupt end. He killed himself in 1927, as did Harry Crandall, who later went bankrupt, a decade later. The Knickerbocker Theatre was a Washington, D.C. movie theater located at 18th Street and Columbia Road in the Adams Morgan neighborhood. It collapsed on January 28, 1922, under the weight of snow from a two-day blizzard that was later dubbed the Knickerbocker Storm. The theater was showing Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford at the time of the collapse, which killed 98 patrons and injured 133. The disaster ranks as one of the worst in Washington, D.C., history. The Knickerbocker Theatre collapse is tied with the Surfside condominium collapse as the third-deadliest structural engineering failure in the United States history, behind the Hyatt Regency walkway collapse and the collapse of the Pemberton Mill. The Knickerbocker Theatre was commissioned by Harry Crandall in 1917. Designed by architect Reginald Geare, it had a seating capacity of 1,700. In addition to serving as a movie theater, it also served as a concert and lecture hall, with ballrooms, luxurious parlors, and lounges.

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, October 05, 2021

“Swampoodle” was the term originally applied to the settlement along H Street near the Tiber (between North Capitol and First Street, East), and finally it included Pearce’s meadow, a great hunting ground extending to the boundary of the city. … In recent years the eastern line of the ‘poodle’ has been contracted to the limits of G, K, Fourth, East, and First Streets, West. . . .” The name was applied in the 1850s, although when exactly is unknown. Swampoodle was a neighborhood in Washington, D.C. on the border of Northwest and Northeast in the second half of 19th and early 20th century. This neighborhood is no longer known as Swampoodle and has been replaced in large part by NoMa.

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, September 07, 2021

The date was April 15, 1848. The place: Washington’s Potomac River waterfront. The incident prompted angry debate in Congress and it helped end the slave trade in the District of Columbia. It is no coincidence that the next day, April 16, would be celebrated henceforth as Emancipation Day. But for many white people of the time, the incident triggered an angry reaction. Church bells and fire alarms signaled revulsion beyond the scope of anyone’s imagination.

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, September 07, 2021

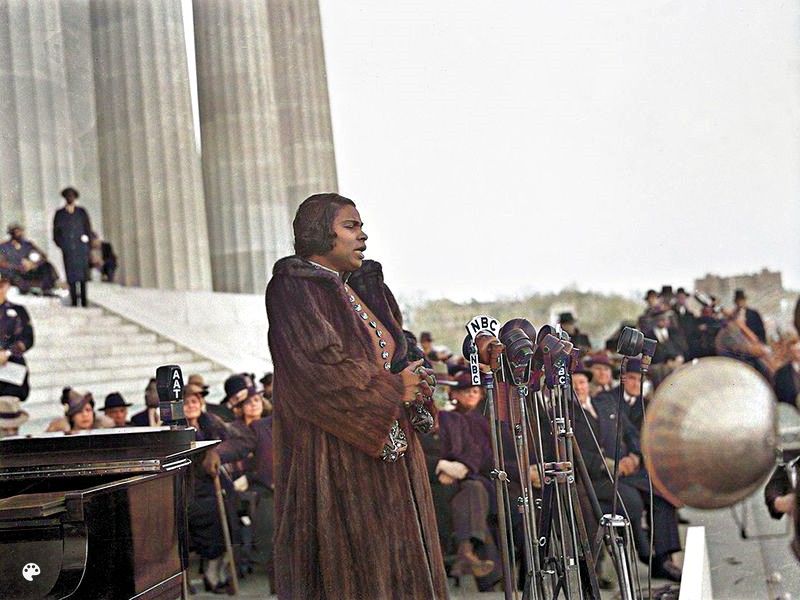

It was Easter Sunday on April 9, 1939. One of the world’s greatest singers, contralto Marian Anderson, had been denied permission to sing at Constitution Hall, owned by the Daughters of the American Revolution, because of her race. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt quit the D.A.R. over the racist action and helped change the venue to the Lincoln Memorial. The incident placed the respected contralto into a spotlight unusual for a classical musician of the time. 75,000 people were in the audience that day. She was terrified. Later, she wrote: “I could not run away from this situation. If I had anything to offer, I would have to do so now.” And some one-hundred thousand Washingtonians joined Ms. Roosevelt in giving the stuffy organization the finger.

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, September 07, 2021

For millions of Americans who lived outside the big cities in the first part of this century, Chautauqua was one of the biggest events of every year, with its combination of adult education, moral uplift, entertainment, and a community-wide social gathering of a sort that we no longer experience. The Chautauqua idea and name came from the original Chautauqua Institution, founded in 1874 on the shore of Lake Chautauqua in western New York State and still going strong. The original Chautauqua and its early offshoots were summertime retreats of two weeks duration or more, during which adults could continue their educations with informative and inspirational lectures and performances of good music. There were also participatory exercises, such as choral singing, and special activities for the youngsters. The Chautauqua idea spread quickly, with similar assemblies established around the country in the next years. By the tum of the century, scores of Chautauquas were being held each summer. These early Chautauquas were of the so-called "independent" variety-that is, they were organized and managed locally, and the speakers and other talent were chosen and engaged by the local committee. Frederick Crane, contributor Univ.Illinois The amusement park was one of the larger establishments of its type in the Washington, D.C. area, and remained popular well into the late 1940s. It was during this time much of the Art Deco Architecture associated with Glen Echo Park was built. Art Deco represented elegance, glamour, functionality, and leisure, and was especially appropriate for the modern rides of amusement parks. For millions of Americans who lived outside the big cities in the first part of this century, Chautauqua was one of the biggest events of every year, with its combination of adult education, moral uplift, entertainment, and a community-wide social gathering of a sort that we no longer experience. The Chautauqua idea and name came from the original Chautauqua Institution, founded in 1874 on the shore of Lake Chautauqua in western New York State and still going strong. The original Chautauqua and its early offshoots were summertime retreats of two weeks duration or more, during which adults could continue their edu cations with informative and inspirational lectures and performances of good music. There were also participatory exercises, such as choral sing ing, and special activities for the youngsters. The Chautauqua idea spread quickly, with similar assemblies established around the country in the next years. By the tum of the century, scores of Chautauquas were being held each summer. These early Chautauquas were of the so-called "independent" variety-that is, they were organized and managed locally, and the speakers and other talent were chosen and engaged by the local committee. Frederick Crane, contributor Univ.Illinois

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, September 07, 2021

Theaters of the 19th Century Theater design and technology changed as well around the mid-19th century. Candlelit stages were replaced with gaslight and limelight. Limelight consisted of a block of lime heated to incandescence by means of an oxyhydrogen flame torch. The light could then be focused with mirrors and produced a quite powerful light. Theater interiors began improving in the 1850s, with ornate decoration and stall seating replacing the pit. In 1869, Laura Keen opened the remodeled Chestnut Street Theater in Philadelphia, and newspaper accounts describe the comfortable seats, convenient boxes, lovely decorations and hangings, excellent visibility, good ventilation, and baskets of flowers and hanging plants. Theater crowds in the first half of the 19th century had gained a reputation as unruly, loud and uncouth. The improvements made to theaters in the last half of the 19th century encouraged middle- and upper class patrons to attend plays, and crowds became quieter, more genteel, and less prone to cause disruptions of the performance. Fanny Brown in costume with American flag Well into the mid-19th century, American theaters continued to be strongly influenced by London theater. Many actors and actresses of this period were born and got their professional start in England. Plays performed tended to follow the English classical tradition, with Shakespeare's plays and other standard English plays remaining popular. However, American-born playwrights and actors began to have an influence, and contemporary plays began to be performed regularly as well. Prior to the 1850s, a theater bill might include five or six hours of various entertainments, such as farces, a mainpiece, an afterpiece, musical entertainment, and ballet. Music was an important component of early American theater, and plays were often adapted to included musical numbers. In the 1850s, the number of entertainments on a theater bill began to be reduced, first to two or three and, later, to one main feature only. Acting styles in the early 19th century were prone to exaggerated movement, gestures, grandiose effects, spectacular drama, physical comedy and gags and outlandish costumes. However, from the mid-19th century, a more naturalistic acting style came into vogue, and actors were expected to present a more coherent expression of character. Subject matter of new plays was more often drawn from contemporary social life, such as marriage and domestic issues and issues of social class and social problems. Another favorite form in 19th-century theater was the burlesque (also called travesty). The plays of Shakespeare, especially those in the regular repertory of the legitimate theaters, were a favorite target. Many actors were known primarily for their comedic and burlesque acting talents. Structure of Theater Companies Joseph Jefferson, III, in the role of Rip Van Winkle Plays and Other Entertainments in the 19th Century Theater No one person invented cinema. However, in 1891 the Edison Company successfully demonstrated a prototype of the Kinetoscope, which enabled one person at a time to view moving pictures. By 1894 the Kinetoscope was a commercial success, with public parlors established around the world. The first to present projected moving pictures to a paying audience were the Lumière brothers in December 1895 in Paris, France. The earliest films were in black and white, under a minute long, without recorded sound and consisted of a single shot from a steady camera.

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, September 07, 2021

As Washington prepared for the civil war in 1859, some Washingtonians were making other plans. A group of mostly government clerks founded the Washington Base Ball Club and named it the Washington Nationals. Through tournaments, public relations efforts, newspaper coverage, and a "grand tour o the west," the Nationals gave the public something to feel positive about during the 1860s and helped make baseball an important part of American identity. In 1859, DC was a city on the verge of civil war, and the 1860 presidential election dominated the political stage and the nation's newspapers. However, the election and sectional tensions were not the only topics covered, and, in 1859, reporters were increasingly covering New York'sbaseball games and noting the creation of new teams. It was against this backdrop that a group of mostly federal government employees decided to follow their counterparts up north and form an organized baseball team--the Washington Nationals. A careful review of the activities of the Nationals during the key decade of the 1860s clearly illustrates that they were significant to the development of the national pastime.

- Posted by : Tom Hendrick, November 29, 1921

Margaret Gorman was a junior at Western High School in Washington, D.C. when her photo was entered into a popularity contest at the Washington Herald. She was chosen as “Miss District of Columbia” in 1921 at age 16 on account of her athletic ability, past accomplishments, and outgoing personality. As a result of that victory, she was invited to join the Second Annual Atlantic City Pageant held on September 8, 1921, as an honored guest. There she was invited to join a new event: the “Inter-City Beauty” Contest. She won the titles “Inter-City Beauty, Amateur” and “The Most Beautiful Bathing Girl in America” after competing in the Bather’s Revue. She won the grand prize, the Golden Mermaid trophy. She was expected to defend her positions the next year, but someone else[who?] had attained the title of “Miss Washington, D.C.,” so she was instead crowned as “Miss America.” She is the only Miss America to receive her crown at the end of the year. Gorman was the lightest Miss America at 108 pounds until 1949, when Jacque Mercer of Phoenix, Arizona, weighed in at 106 and won the title. Gorman later said: “I never cared to be Miss America. It wasn’t my idea. I am so bored by it all. I really want to forget the whole thing.” She still owned the sea green chiffon and sequined dress that she wore in the 1922 competition.