Throughout its history, Washington, DC has been the destination of demonstrators seeking to promote a wide variety of causes. The January 6th attack on the capitol is just the latest example.

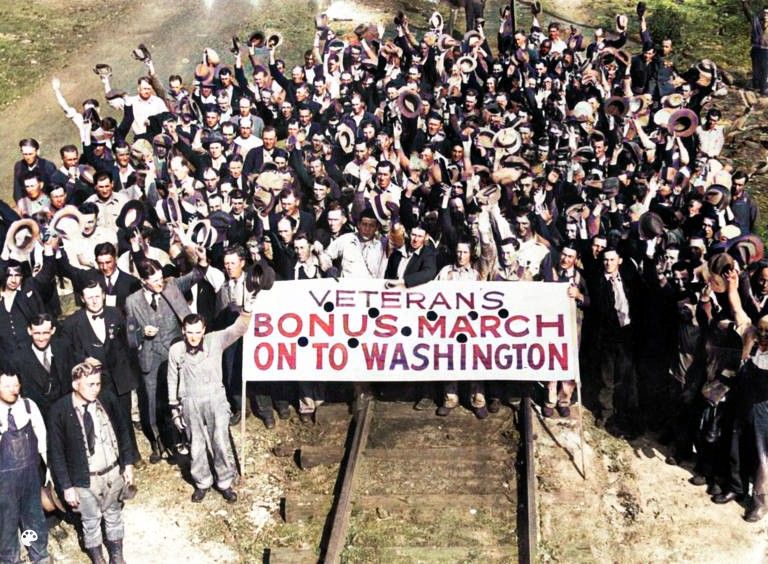

In March of 1932, another large group of protestor/patriots came demand the Bonus pay they’d earned during World War One. After victory in World War I, the US government promised in 1924 that servicemen would receive a bonus for their service if they could wait until 1945. In March of 1932, another large group of protestors came to demand the Bonus pay they’d earned during World War One.

The Great Depression was on, and the U.S. Treasury was strapped for cash. By 1932, the Depression was dragging on, with no end in sight. Out of sheer desperation, some of the veterans decided to march on Washington to ask for the bonus right away.

They began a long trek to Washington aboard a freight train, loaned to them for free by the rail authorities. Others drove or hitched rides. Some even walked. They camped out in homemade shantytowns. The major sites included 12th Street and B Street, NW (the latter is now Constitution Avenue), 3rd Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, and the largest, 30-acre site on the Anacostia Flats.

It turned into a fiasco. The veterans were attacked by their own Army, led by General Douglas McArthur and a major-who-would-be President, Dwight D. Eisenhower.

The US House of Representatives did in fact vote to provide the bonus, but the US Senate rejected it. President Herbert Hoover had promised the veto the bill, anyway. Things stayed in an unsettled condition for the next few weeks, with some veterans leaving but even more arriving until their number reached somewhere between 10,000 and 20,000.

On July 28th, the veterans violently were run out of town. The disgraceful episode was another reason that Hoover was forcefully de-elected. As for the newspapers of that day, the Associated Press released a list briefly describing their editorial reactions. Out of 30 papers, 21 more or less supported the government’s response. The Ohio State Journal, of Columbus, Ohio, for instance, wrote: “President Hoover chose the course that Lincoln chose, that presidents have always chosen.” On the other hand, the Chicago Herald and Examiner, referring to President Hoover by name, called his actions “sheer stupidity” that was “without parallel in American annals.”

Four years later, in 1936, the veterans did get their bonus, when Congress voted the money over President Franklin Roosevelt’s veto. In 1944, while World War II was still raging, Congress passed the G.I. Bill, to assist veterans in receiving a higher education.

Sources and Related Links